![]()

A PAINTER WITH NEEDLES

The artistry of Korean embroiderer Young Yang Chung

by Morris Rossabi

|

Korean embroiderer Young Yang Chung's enthusiasm for her art is infectious. In addition to creating her own exquisite works, Chung is dedicated to increasing interest in and awareness of embroidery and the textile arts, and to that end is involved in a dizzying array of projects: she is assisting with the planning of the Chung Young Yang Embroidery Museum at Sookmyung Women's University in Seoul, named in her honor, and is organizing the inaugural exhibition, scheduled to open in May 2004; she is the curator of an exhibition of Korean embroidery, including her own work, that will go on view at the Asia Society Museum in New York in the spring of 2005; her book Painting with a Needle, which includes an overview of East Asian embroidery as well as descriptions of stitchery techniques and instructions for nineteen embroidery projects, will be published by Harry N. Abrams this July, to be followed by The Arts of East Asian Embroidery, a more in-depth analysis of the history of East Asian embroidery, scheduled for publication in 2004. From the age of fourteen, Chung has produced, as she aptly notes, "paintings with a needle." The exuberance with which she describes Korean |

|

|

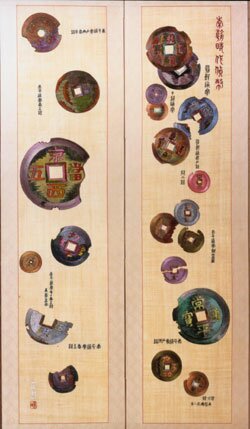

detail from Ancient Coins, a ten-panel screen |

|

Korean and Chinese specialists had too often paid exclusive attention to painting and scorned the textile arts. Because women often produced textiles, the "craft" was deemed to be functional, with limited intellectual and aesthetic appeal. Traditionally, the Chinese said that "men farmed and women wove." Fashioning of textiles was part of a woman's employment and was in the domain of work, not art. Though textiles could be elaborately woven or embroidered and could be emblazoned with beautiful colors and captivating motifs, they were not invested with the intellectual and spiritual content of painting and sculpture. Their design and radiant colors could be enjoyed, but they could never overcome their functional origins (unlike gardening, whichas art historian Craig Clunas, author of Fruitful Sites: Garden Culture in Ming Dynasty China, has shownbegan as a functional pursuit, by both men and women, but by the late Ming dynasty had evolved into an aesthetic expression inextricably linked with status). |

|

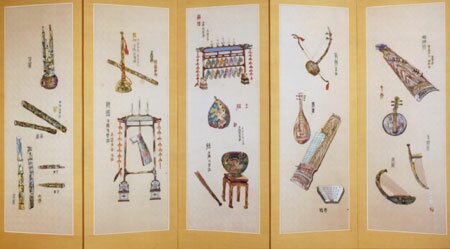

Young Yang Chung, seated in front of the Traditional Musical Instruments screen, embroidering with silk thread that she hand-twists from silk filaments |

Chung has devoted her career to enhancing embroidery's image. In her first book, The Art of Oriental Embroidery (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1979), one of the primary works in this field, she challenged the notion that textiles are minor arts. A brief historical overview enables her to assert that the embroideries on silks and satins produced in China as early as the Warring States period (475-221 BCE) were highly valued. The elite employed embroiderers, most of them women, to create costumes, bridal robes, screens, and wall hangings. Later, during the Tang dynasty (618- 907), Buddhist and Daoist monks recruited both male and female textile workers to fashion robes and banners, including mandalas. Still later, during the Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) eras, the Chinese imperial court drafted a sizable contingent of embroiderers to create the five-clawed dragon robes for the emperor and the four-clawed ones for the immediate imperial family. Chinese embroidery

|

|

detail from Traditional Musical Instruments, a ten-panel screen

(photo ©2002 by John Bigelow Taylor, N.Y.C.) |

The seminal exhibition "When Silk was Gold," which opened at the Cleveland Museum of Art in October 1997 and then at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in March 1998, corroborated Chung's view. The show revealed that the Chinese dynasties of Tang and Song (960-1279) and the non-Chinese rulers of the Liao (907-1125), Jin (1115-1234), and Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties highly valued textiles and innovated with the so-called kesi silk tapestry and the "cloth of gold," which was woven with silk and gold thread. Further confirmation of Chung's thesis is the large bureaucracy established to oversee textile production, particularly during the era of Mongol rule in China. The Yuanthe Mongol dynastyset up a Weaving and Dyeing Office, a Gold Brocade Office, an Embroidery Office, and a Bureau for Patterned Satins, among other agencies, to cater to the textile needs of the imperial court and its officials.

|

However, Chung's own life and career yield the most important proof of the traditional and continuing aesthetic appeal of embroidery. Born and raised in Seoul, she first learned how to embroider from a half-Russian, half-Korean teacher. But during the difficult years of the Korean War, Chung's family was evacuated from Seoul to her father's hometown in Chungchong Province, about 150 miles southwest of the capital. Known as Stone Village, it had a population of fewer than one hundred people. Because of the training she had already received in Seoul,she was adept enough at the age of |

|

detail from Unified Korea, a ten-panel screen

(photo ©2002 by John Bigelow Taylor, N.Y.C.) |

After three years, her family moved back to Seoul. There she continued her education, and embroidery was part of the school curriculum. After completing her studies, she continued to embroider, entering whatever competitions she could, and also began teaching embroidery. Her skill and her remarkable artistry were soon recognized. An advocate of training young women in a vocation, she set up the International Embroidery Institute in 1965. She says she took students in, even though in those difficult years she barely had enough to support herself. In 1967, the Korean government requested that she organize the Women's Center, a facility where the young unemployed homeless women who were flocking to the city from the countryside could learn embroidery. At that time, the economic situation was poor, and the

|

country was seeking ways to increase exports. Chung traveled overseas looking for markets for her students' work. Her first success was in Japan, where her students' hand-embroidered handkerchiefs were sold in Tokyo department stores. Also in 1967, the Korean president's office commissioned her to craft screens for the presidential mansion; soon orders from Japan, Egypt, and the United States came in, keeping Chung and her students busy. Migrating to the United States in the 1970s, Chung sought both to expand her own knowledge of the East Asian tradition of embroidery and to foster an appreciation of the art in her adopted land. She earned a Ph.D. at New York University, with a dissertation on the history and techniques of Chinese, Korean, and Japanese embroideries. Simultaneously, she devoted considerable time and effort to the study of Western and Eastern embroideries in the Textile Study Room at the |

|

detail from Homecoming, a ten-panel screen

(photo ©2002 by John Bigelow Taylor, N.Y.C.) |

Metropolitan Museum of Art. Armed with knowledge of the history of East Asian embroidery and with her own creations in this medium, she set forth on a campaignthrough lectures, demonstrations, writings, teaching, workshops, and exhibitions of her workto develop appreciation of an art often stigmatized as "women's work." A tireless advocate of and proselytizer for a new and elevated conception of the embroiderer's art, she traveled from Australia to her beloved Korea to Europe lecturing about and demonstrating the techniques and motifs of ancient and modern East Asian embroidery. Amazed by the trajectory of her own life and career, she writes that "small needles and homespun silk threads proved to be powerful, life-changing tools that provided me with a viable vocation as well as an expressive and rewarding creative outlet." The effortless, skillful, and incredibly speedy way she twists thread belies her modesty about her work with "small needles and homespun thread."

|

Chung's works have been the best advertisements for her crusade on behalf of embroidery. Eastern patrons were the first to recognize her talents, and even before she initiated her academic career, her embroideries were in the collections of the Korean president's residence, and in the palaces of the shah of Iran and the premier of Malaysia. The quality of her embroideries quickly attracted attention elsewhere, leading to commissions to produce works for the presidential palace in West Germany and as far away as the official residence of the mayor of Baltimore. After her move to the United States, the Metropolitan Museum of Art and the Smithsonian Institution added her embroideries to their collections. Though some of Chung's paintings with a needle are conceived for small frames or small spaces, large-scale screens dominate her studio. Because she needs one and a half to two hours to complete one square inch, she |

|

|

detail from Traditional Musical Instruments, a ten-panel screen

(photo ©2002 by John Bigelow Taylor, N.Y.C.) |

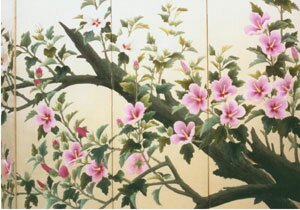

Her most characteristic embroideries depict plants and animals, all of which have reverberations in Chinese and Korean cultures. Her works illustrate her assertion that "the ornamental vocabulary and color schemes used by East Asian artists are replete with

| symbolism." A four-panel screen of a white crane, a symbol of longevity in East Asia, embodies this reaffirmation of the important touchstones of Chinese and Korean culture. The complicated use of three varieties of gray for the neck yields a realistic portrait of the actual colors. A depiction of a Rose of Sharon, the national flower of Chung's country of birth, is shaped in the form of the map of Korea. This imaginative construction, with branches extending to denote the outline of the Korean peninsula, links her to her native land. Finally, Chung has produced a bright and shiny |  |

|

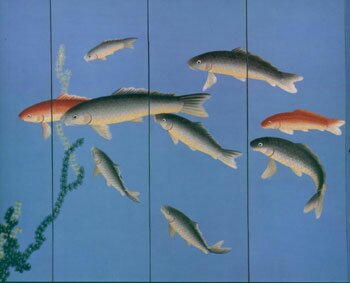

detail from Unity, a ten-panel screen

(photo ©2002 by John Bigelow Taylor, N.Y.C.) |

This extraordinarily bright rendering of fish, which are suffused with symbols that resonate with East Asian traditions, reflect Chung's inextricable bond with and love for embroidery, a passion that many observers of her work will share.

Morris Rossabi is the author of Khubilai Khan and a forthcoming book on China's national minorities.

by Young Yang Chung will be published by Harry N. Abrams in July.