![]()

TAIWAN'S TAI-GU TALES DANCE THEATER

by Caroline Herrick

| The opening of The Life of Mandala contains all the signature elements of Taiwanese dancer Lin Hsiu-Wei's choreography. A male dancer, who happens to be Lin's husband, Wu Hsing-Kuo, enters the darkened stage in silence, his body illuminated by the candle he carries. He then begins a slow chant. It is not until after several minutes, when the lights gradually come up, that one realizes he is not alone on stage. Behind him are a row of eight dancers each wrapped, mummy-like, in gauzy fabric. The fabric covers their faces, as well as their bodies, |  |

|

Part One of The Life of Mandala |

The Life of Mandala, which had its New York premier at the Joyce Theater in early February, was the first dance Lin Hsiu-Wei choreographed for the Tai-gu Tales Dance Theater, the company she founded in Taipei 1988. The ninety-minute dance, which is performed without intermission, had already been presented to audiences in Taiwan, France, Germany, and Holland, as well as at the Spoleto Festival in South Carolina, to critical and popular acclaim, before being chosen by the Joyce for the company's first appearance on its stage. The inspiration for the work, and the impetus for Lin to start her own company, was the tragic death of a frienda young stage designer who fell from a lighting truss as he was setting up for a production by Contemporary Legend Theater, a theater company founded by Lin's husband.

Lin Hsiu-Wei and Wu Hsing-Kuo, who were married in 1980, met when they were both principal dancers with Cloud Gate Dance Theater, often referred to as Asia's leading

|

contemporary-dance company. The multitalented Wu, recognized as one of the leading Peking opera performers of his generation, left Cloud Gate in the early 1980s to join a Peking opera troupe and then, in 1986, founded his own company, which uses the style and techniques of Peking opera to present adaptations of Western classical plays, such as Hamlet, Macbeth, and Medea. Lin and Wu, who are in their early forties, are a formidable team: she is a producer for Contemporary Legend Theater, and he is not only principal dancer but also artistic advisor for his wife's company. Lin describes the death of their friend and colleague as a defining moment in their lives, a moment that changed their fundamental attitudes and outlook. To find solace and meaning after such a tragedy, she turned to her parents' religion, Buddhism, and also began to read Indian philosophy and the poetry of Rabindranath Tagore. |

|

Lin Hsiu-Wei

(photo by Caroline Herrick) |

The Life of Mandala is divided into four parts, each of which explores one of the states the voyager through life, in this case performed by Wu Hsing-Kuo, must pass through. The first part, "Sublimation," depicts waiting for birth or rebirth. When I asked Lin which, during an

| interview in New York two days before the opening performance at the Joyce, she replied, "Both." Wu moves among the mummy-like dancers as they slowly emerge from the shadows and come to life in what seems like a primordial awakening, only to fade gradually into darkness again. The second part, entitled "The World of Desires," explores sexual desire, from chaste attraction to unbridled lust. At one point, as Lin lies spread-eagle on her backa pose that while suggestive does not, in this context, seem vulgarWu regally glides toward her as if being pulled across the stage by an invisible string; when he reaches her, he bows down |  |

|

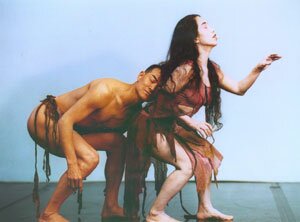

Wu Hsing-Kuo and Lin Hsiu-Wei in The Life of Mandala |

In conversation, Lin often uses the term "childlike" to describe the movements in her choreography. Perhaps the word is apt for someone who started out as a self-taught dancer, who during her childhood in Keelung, a port some twenty miles northeast of Taipei, loved nothing more than to create dances for herself and her friends, and who passed the entrance exam for the dance department at Taipei's Chinese Cultural College by performing a dance of

|

her own design, despite never having taken any dance classes, wearing a costume she made herself. Lin Hsui-Wei began her formal dance training when she entered the college at the age of fifteen. There she studied under Lin Hwai-min, founder of the Cloud Gate Dance Theater (the two dancers are not related). Lin Hwai-min had recently returned from the United States, where he had studied under Martha Graham and Merce Cunningham, and was just setting up his company. By her third year in college, Lin Hsui-Wei had been invited to join Cloud Gate. She remained with the company for ten years, from 1976 to 1986, becoming a principal dancer, choreographer, and rehearsal mistress. In 1986, Lin received a Fulbright |

|

Lin Hsiu-Wei and Wu Hsing-Kuo demonstrating a movement

(photograph by Caroline Herrick) |

| The third part of The Life of Mandala, although entitled "Awakening," actually seems to be about death and is, again, performed mostly in darkness. In one of the more memorable sequences in this section, each of the male dancers, in turn, falls backward from a standing position flat onto his back. The final section, "Buddhist Chanting," is the only one that takes place in the lightin fact, the subtitle is "The light of heaven penetrates our hearts and our mind"and represents Nirvana, or the joy that supersedes suffering. The dancers wear |  |

|

Part Four of The Life of Mandala |

The costumes for The Life of Mandala were designed by Yip Kam-Tim, also known as

|

Timmy Yip, the costume designer for Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (for which he received an Academy Award nomination). The lively, eclectic score, composed by Shih Chieh-Yun, incorporates a number of different musical styles, including gamelan, tabla, and sequences with a distinctly African beat. Lin choreographed the entire dance before commissioning Shih to write the music. Lin says she often finds music distracting when choreographing, and when she returned to Taiwan from America in 1987, she choreographed a duet without music, The Myth of the Late 20th Century, which she and Wu perform in silence. |

|

Wu Hsing-Kuo and Lin Hsiu-Wei in their Taipei studio

(photograph by Caroline Herrick) |

Through their respective companies, Lin Hsiu-Wei and Wu Hsing-Kuo are contributing to Taipei's thriving art scene by creating art forms that appeal to "the man on the street," as well as to more sophisticated audiences. Tai-gu Tales Dance Theater is one of a growing number of companies in which influences from East and West are being reexamined and incorporated into distinctive, original forms of artistic expression. The Life of Mandala is just one of the eleven productions in the company's repertoire, and is one of threethe other two are The Back of Beyond and Obsession of the Stonethat have been presented to audiences outside of Taiwan to date. The company is drawing enthusiastic young audiences into Taiwan's theaters, and as its international reputation grows, one can only hope that audiences abroad will have the opportunity see a broader range of works from its repertoire.

Caroline Herrick is the editor of Persimmon.

The Tai-gu Tales Dance Theater performs in Taipei and on tour throughout Taiwan. It will tour Canada in 2004, appearing at the National Arts Center in Ottawa on January 30 and 31, and at the Harborfront Center in Toronto from February 3 to 7. Additional performances at the Centre Pierre-Péladeau in Montreal from February 12 to 14 are in the planning stages.