![]()

HOW JAPAN PICTURED THE WEST

Nineteenth-century woodblock prints from Yokohamapart popular art, part

breaking news report

by Suzanne Charlé

Nineteenth-century Yokohama came to life briefly in New York City at the end of March, when an important collection of Japanese prints was put on the block at Christie's. The sale offered Americans an excellent chance to see how they were viewed after Commodore Perry's squadron first arrived in Japan in 1853 and pressured the Japanese government to negotiate a trade treaty, thus opening to Westerners the previously closed country. And for those familiar with the history of the period, it also offered a good look at how graphic images are manipulated when the wills of nations collide. News media then, as now, served various masters.

|

|

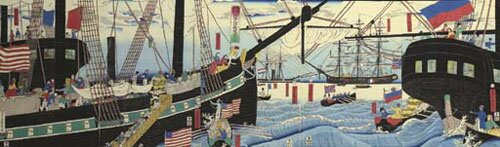

Hashimoto Sadahide, Western traders transporting merchandise at Yokohama, 1861 |

Of the 430 ukiyo-e (woodblock prints) in the collection, 28 were scenes of Yokohama, one of six sites in all of Japan eventually designated as open ports, thanks to Perry's gunboat diplomacy. (For those who missed the viewing, the Metropolitan Museum of Art has a good collection, assembled by the late Lincoln E. Kirstein, the former general director of the New York City Ballet, as, of course, does the Yokohama Museum.)

After it was opened to Western powers in July 1859, the tiny fishing village of Yokohama quickly grew into an international port. Julia Meech, senior consultant in Christie's Japanese department and author of The World of the Meiji Print: Impressions of a New Civilization, writes that Yokohama was selected not only because of its deep harbor and its proximity to the capital, Edo, but also because it was off the main Tokaido highway (which ran from Edo to Kyoto), where "anti-foreign samurai and displaced swordsmen might provoke incidents." The foreigners were kept out of harm's way on the rectangle of land about two miles square, cut off from the rest of Japan by sea, swamp, and creek. People could enter only by boat or over four bridges, which opened at sunrise and closed at sunset.

This enforced separateness only whetted the locals' desire to know more about the men with big noses and rough manners. Publishers of ukiyo-e, who for decades had been offering prints on popular subjects of the daya beautiful courtesan, a new Kabuki play, popular tourist siteswere quick to recognize a new market. They commissioned fifty-three artists to illustrate the scenes, which were sold in the cities to an eager public; itinerant dealers hawked the bright- colored scenes of the bustling port throughout the countryside.

Part popular art, part pre-photo newsbreaks, the Yokohama ukiyo-e were an immediate success: According to Meech, some eight hundred designs that included foreigners (eighty percent of all Yokohama scenes) were issued during 1860 and 1861this "despite the fact that there were only 34 Western merchants living in Yokohama in 1860 and no more than 100 or 200 Western residents (mostly) English by 1862."

Scenes showed the plans of the island, the busy harbor life, interiors of the houses that the Westerners quickly built, their odd style of dress, the way sailors and traders amused themselves on shore.In a five-part print by Hashimoto Sadahide entitled "Western traders transporting merchandise at Yokohama," (above) we see the "black ships" in the harbor, each flying a flag of one of Japan's new trading partners: Russia, Britain, France, the Netherlands, and the United States. Lavishly dressed Western women are ferried by longboats to tour the three- masted schooners, while porters busy themselves loading and unloading cargo. Sailors scurry up the rigging; cannons point ominously from gun ports.

|

|

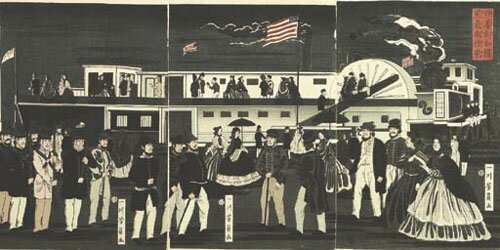

Utagawa Yoshikazu, The transit of an American steam locomotive, 1861

(courtesy of Christie's) |

A triptych by Utagaw Yoshitora, "Picture of amusements of foreigners in Yokohama," is filled with Westerners at their leisure: women in hooped skirts greet each other in the street as a merchant is taxied along in a rare two-horse carriage; a woman in a long skirt rides past, sitting sidesaddle (a site never seen in Japan before the Westerners arrived). Bearded men (looking like Abraham Lincoln, who was nominated by the Republican Convention just as the Japanese embassy arrived in Washington in 1860) sit on chairs, watching a Kabuki play. A black sailor (his face blue) wanders near a shop, carrying a sack of unknown treasure. Meech observes that the pleasant ambience was, for the most part, a fantasy: There were only a handful of Western women in the port, and they tended to be housebound; most of the buildings were shabby wood huts.

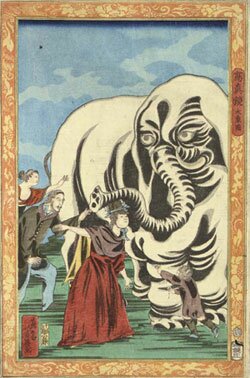

In his forward to Meech's book, historian Edward Seidensticker (a self-described "fancier" of the ukiyo-e woodcuts) notes: "The pleasure in new things, railroads and violins and buttons and bustles, lends itself beautifully to graphic representation." And so it does in these prints, in which Japanese got to see for the first time strange animalselephants, tigers and camels brought to the island nation by the foreigners. One Portuguese entrepreneur brought a three-year-old female India elephant, which caused a commotion when it was exhibited. One reporter crowed that the beast had "a shape like a large mountain," and went on to promise: "For those who see it the seven misfortunes will decrease and the seven fortunes will grow." Not surprisingly, the poor elephant was the subject of a number of prints, including a charming one attributed to Utagawa Yoshiiku (below), but, in fact, believed to have been carved by his thirteen-year-old son. (Specialists point out, as proof, the roughly exuberant modeling of the elephant, the crude curls of the woman's hair.)

Not content with images only of Western life in Yokohama, the artists offered the public scenes of cities and inventions in far-off lands: a view of the Thames with a tropical red sunset; a scene of France, with Fuji-esque mountain and palm tree. Some details were borrowed from sketches from visitors, others from engravings in copies of journals like the Illustrated London News. When images were not quite clear or were not available, the artist would use his imagination, as in the dockside night scene by Utagawa Yoshikazu entitled "The transit of an American steam locomotive" (above). Here, a jubilant dockside crowd makes pleasantries near a hybrid of a paddle-wheel steamship and railroad locomotive.

| In fact, the Yokohama prints show a make-believe world in which there are only good times and exciting new inventions, and like the hybrid paddle-wheel locomotive, the version of life they presented was largely made-up, myths fed to a public that had no other means of information, by a media intent on making money, at the behest of the desires of the Japanese government (which could, and did, censor images it didn't like) and the invading merchants. The fact was that the Westerners were an occupying force, and the Japanese government was too weak to force them out. The supposed cordiality of the open policy was undercut by laws that made befriending a Westerner a treasonable act. Many Japanese were angry with the enforced, uneven trade, and in the years immediately following the opening, the British legation was attacked twice, the Americans' office was burned to the ground and one of its officials assassinated in Edo, and when a fire broke out, a Prussian commodore put troops on shore to protect the settlement; the arsonist alarm proved false, but the worry of the occupier in an occupied land was very real. |  |

|

Utagawa Yoshiiku, Camera view: picture of a large elephant, 1861 |

At the same time that the cheerfully colorful Yokohama prints were showing a world of wonder and new inventions, a letter by a British minister gave a much darker view of the outpost. After visiting in 1860, the Right Reverend Bishop Smith of Hong Kong decried the "disorderly elements of California adventurers, Portuguese desperadoes, runaway sailors, piratical outlaws and the moral refuse of European nations." He sadly added, "Europeans in every part of the world too often carry with them a contemptuous dislike of the aboriginal natives, and demean themselves with the air of a superior and conquering race even in countries where they are strangers barely tolerated by the governing powers and are regarded (sometimes with the Semblance of real truth) as inferiors in civilization."

The tale of the Yokohama prints is a cautionary one: their popularity in Japan faded with the introduction of the photograph, and within two decades, the Japanese (who, in the woodblocks and in the European-dominated port, had been kept in the background) had supplanted the foreign shopkeepers and challenged the Western traders. Occupied Yokohama had been a tough but important school, and as Lafcadio Hearn was quick to point out, "The Japanese had been learning wonderfully well." Today, virtually all of the collectors of Yokohama prints are Western.

Suzanne Charlé frequently writes about Asian arts and culture for the New York Times, The Nation, and the Ford Foundation Report.