![]()

THE REINVENTION OF TRADITION

The paintings and calligraphy of Taiwan artists Liu Kuo-sung, Hsiao Chin, and Tong Yang-tze

by Yi-li Kao

Since the lifting of martial law in 1987, Taiwan has enjoyed an unprecedented freedom of expression that has resulted in a blossoming of the arts, which are now open to all concepts, mediums and schools, from the past and the present, the East and the West. In the midst of such lively and fresh work by younger artists, however, there remains the lingering influence of the modernist work of their predecessors, who came into prominence during a more repressive period, some three decades earlier. The need to continually reexamine these pioneering artists of the 1960s signifies a strong art-historical consciousness in the seemingly brand-new ideas found in contemporary art in Taiwan.

On view this spring in Taipei's museums and galleries was a celebration of some of Taiwan's most accomplished modern artists, whose work represents perhaps the most rapid and difficult transition yet in the history of Chinese art from the traditional to the modern. In March, the Taipei Fine Arts Museum opened its 2003 selection of "Highlights from the Permanent Collection," which runs until the end of the year, while also showcasing for two months a special exhibition of its latest acquisitions. Both shows included early, groundbreaking, as well as recent work by representative painters such as Liu Kuo-sung and Hsiao Chin. Also featuring Hsiao Chin's work was the Howard Salon's "Special Show of Fine Arts Festival," on view from mid-March to early April, a small exhibition that paid tribute to six recipients of the National Culture and Art Foundation's highest achievement awards for the fine arts. In addition, an extraordinary installation of Tong Yang-tze's large-scale calligraphy could be seen at the spacious National Theatre and Music Halls of the Chiang Kai-Shek Memorial in March; it later traveled around the island.Leading figures of what might be called the second phase of modernism in Chinese art, Liu Kuo-sung and Hsiao Chin were central to the modern art movement in postwar Taiwan. In many ways, and for a long time, this movement was the only collective force striving to consolidate and advance the grand project of modernizing Chinese arta project that had been launched in mainland China at the turn of the twentieth century but was cut short by war

|

and political turmoil. While Liu Kuo-sung maintains the traditional mode of ink painting as the central focus of his work, Hsiao Chin turns more to Western oil and acrylic painting. Despite the different mediums they use, what has governed the art of both painters is the same firm determination to integrate the modern spirit and traditional Chinese sensibilities. Like many others of his generation, Liu Kuo-sung, who was born in Anhui Province in 1932, spent his early youth in constant displacement all over tumultuous, war-stricken mainland China, and eventually fled to Taiwan with the Nationalists in the late 1940s. At the Fine Arts Department of National Taiwan Normal University, the leading art institute of postwar Taiwan, he received academic-based training that combined both the orthodox Chinese literati tradition and the late-nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Western modernisms of postimpressionism, fauvism, and cubism. Frustrated with the stale conventions of guohuathe traditional Chinese ink painting crowned as "national painting" by the newly settled Chiang Kai-shek regimeLiu started out on his path toward revolutionizing Chinese art by first embracing the more lively and boundless practice of Western painting. Upon graduation in 1957, he and several of his classmates founded the Fifth Moon Group. As members of the first modern painters' society on the then still culturally and politically conservative |

|

|

Liu Kuo-song

I Come Here to Hear Heavenly Sound 1960, oil on canvas 79.5 cm x 41 cm private collection (courtesy of the artist) |

American abstract expressionism had a particularly profound impact on Taiwan's postwar painters due to the strong ties between the United States and Taiwan. Liu Kuo-sung recalls that he would frequent the library at the American embassy and absorb every bit of information on the rising New York school of modern art. By the late 1950s, Liu had produced some notable abstract works, such as I Come Here to Hear Heavenly Sound, by creating on canvas the impulsively fluid and textured effects of oil running down randomly shaped plaster. However, around 1961, Liu arrived at a personal milestonewhich was to influence his peers as wellbased on two primary realizations. First, that year, at a special exhibition at the National Palace Museum in Taipei, he was overwhelmed by the vivid, unbounded energy that he saw in Song landscape painting of the eleventh century. Second, the validity of the theory of the "irreplaceability of materials" asserted by modern Chinese architects became apparent to him. Liu came to realize that those supposedly modern qualities of uncontrived spontaneity he had been so fervently pursuing had existed all along at the core of Chinese art. It became clear to him that total rejection of Chinese tradition was not the answer, and that if it was modern Chinese painting that his generation was making an effort to achieve, then it was necessary to begin their search for that within their own rich heritage.

|

From the early 1960s on, Liu Kuo-sung, employing the classical medium of ink and paper, has endeavored to invoke what he considers the modern elements in the Chinese tradition while remaining a keen observer of the latest developments in artistic practices and ideas in the West. Liu's synthesis of East-West polarities is evident in his splendid series of "space paintings," which were inspired by the American moon landings. In his 1970 Moon's Metamorphosis No. 29, Liu pushes Eastern gestural brushwork to an extreme, exploring all the possibilities of this Chinese calligraphic mode, while at the same time deftly adopting the Western idea of collage to create a two-part composition. With the geometric configuration of the planets at once abstract and concrete, Liu Kuo-sung produces a landscape like none ever before |

|

Liu Kuo-song |

Another critical figure in the development of Taiwan's modern art is Hsiao Chin (born in Shanghai in 1935), the driving force of the Eastern Society, founded by a group of young artists in 1957, only a few months after the Fifth Moon Group was established, and like the Fifth Moon Group, also of major importance in the modern art movement in Taiwan. Hsiao and other members of the Eastern Society, all of whom were affiliated with National Taiwan Normal College and had studied with the Japanese-trained surrealist Li Zhongsheng (1912-84), were encouraged by their mentor to strive for a style that would reflect both the time-honored characteristics of Eastern culture and the modern era that it was now entering. Since they were not restricted by form or subject matter, the sources of their paintings were diverse and avant-garde in nature, and included ancient oracle-bone writing, Chinese folk art, surrealism, and dadaism. In the late 1950s, Hsiao Chin received a fellowship to study in Spain; his frequent newspaper articles about European painting were a particularly important bridge to the outside world for Taiwan's artists.

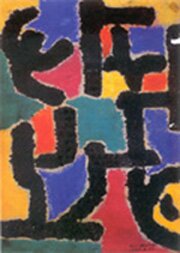

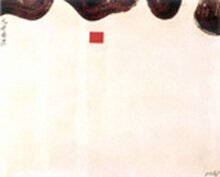

| Hsiao Chin's early work, such as Abstraction, like that of Liu Kuo-sung, showed strong Western influence, in particular from the expressionist painter Paul Klee. Hsiao's move toward Chinese tradition was prompted by his encounters with Western culture in Spain. Hsiao once revealed in an interview that it was not until he witnessed the free form of Art Informel (the European counterpart to abstract expressionism) that he came to recognize similar elementsperhaps even more extremeof such freedom in Chinese art. Nevertheless, Hsiao's return in the early 1960s to the Chinese tradition was not simply a return to Eastern form and style. Rather, he resorted more to a philosophical foundation, as ideas of Zen Buddhism and Taoism became central to his painting.His 1961 painting The Great Site without Boundarya few free-form strokes in black ink and a simple red square on a light |  |

| Hsiao Chin Abstraction No. 2 1955, ink and pastel on paper 40 cm x 29 cm private collection (courtesy of the artist) |

|

Despite their different approaches, both Liu Kuo-sung and Hsiao Chin incorporate in their work elements of modern expression and of a shared, ancient culture. Interestingly enough, it was because of their introduction to Western modern art that these two artists, along with many other painters in Taiwan in the 1960s, were able to come to terms with their native Chinese tradition. In contrast, following a decade after Liu and Hsiao, the female artist Tong Yang-tze, who works exclusively with calligraphy, showed early on more confidence in and ease with the Chinese legacy. |

| Hsiao Chin The Great Site without Boundary 1961, ink on canvas, 80 cm x 100 cm private collection (courtesy of the artist) |

Tong Yang-tze is one of the most innovative calligraphers of her generation. She was born in Shanghai in 1942, and, like Liu Kuo-sung, received academic training in both Chinese and Western art at National Taiwan Normal University; she also studied at the University of Massachusetts, where she earned an M.F.A. in 1970, before returning to Taiwan. Since then, she has exhibited widely in Asia, North America, and Europe. Her work develops, in particular, the painterly qualities of calligraphy, and the renowned scholar and calligrapher Tai Jingnong (1902-90) paid tribute to Tong three years before his death by describing her work as "having reached a new territory where calligraphy and painting meet."

|

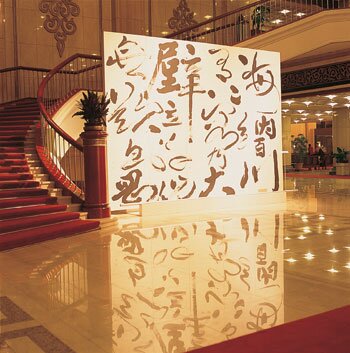

| Tong Yang-tze The Sea receives all rivers; it is large because it is receptive ink on paper, 358 cm x 485 cm (courtesy of the artist) |

Contrary to the graceful and delicate mode of writing often associated with female calligraphers, Tong Yang-tze's style is large and imposing. This may be due, in part, to the fact that her calligraphy derives from the Tang-dynasty master calligrapher Yan Zhenqing (709-785), who was renowned for his upright, sturdy brushwork. Tong's calligraphy usually consists of a short phrase or passage from a classical literary or philosophical text, like the Book of Poetry or Lao Tze. Nonetheless, she is able to render modern interpretations of these classical texts by arranging them in an unconventionaleven shockingshape and order. Often she either enlarges or downsizes certain characters or strokes to produce a dramatic effect that challenges today's viewers to discover on their own some new approach to reading both the texts and the art. Such deconstruction of tradition through distortion and transformation of forms has been recognized as an important contribution to the revival of calligraphy by contemporary East Asian artists.

| Tong Yang-tze's exhibition at the Chiang Kai-shek Memorial Hall, entitled "With Words Come Freedom," contained ten examples of her recent work; several of them as large as the hall's entrywaythe largest was eight meters wide (and was drawn with a very big brush). Charged with overflowing energy, her calligraphy bears a striking resemblance to the pictographic images of some |  |

| Tong Yang-tze Hongjianyupan ink on paper, 182 cm x 364 cm (courtesy of the artist) |

Conditioned by the complex national, historical, and cultural struggles of modern China, it is a uniquely Chinese modernism that modern artists in Taiwan have come to achieve. Taiwan's artists were the first after the May Fourth movement to critically examine Western painting and to actively reinvent the Chinese tradition. Liu Kuo-sung, Hsiao Chin, and Tong Yang-tze have not only made an impression on Western audiences, but also played a key role in the recent revitalization of Chinese art through their influence on contemporary artists in Taiwan and beyond.

Yi-li Kao is a Ph.D. candidate in comparative literature at the University of California, San Diego, who has done extensive research on the poetry and painting of postwar Taiwan.