![]()

EVENING THE SCORE

Lagaan, a period film with an anti-imperial narrative

reviewed by Veena Naregal

What would popular Indian culture be minus the mania for cricket and films? On the subcontinent, cricket and cinema are not "just" entertainment; to most Indians, these pastimes evoke passions and supply pleasures that lie at the very core of their identity and experience as modern beings. Tapping simultaneously into the huge following these pursuits enjoy, Ashutosh Gowariker's Lagaana stirring tale of resistance and triumph, in which the humble inhabitants of a drought-hit village take on the unjust might of the British Raj through a game of cricketwas, it seems, a film waiting to be made.

| Set in 1893, Lagaan has none of the nostalgia for empire that informs many British or American films depicting the period. Champaner, a parched village in central India, has had no rain for two years. But Captain Russell (Paul Blackthorne), the commander of the local British regiment and a pitiless white supremacist, shows no remorse in collecting tribute from the local raja, who, in turn, has to acquire it as land tax (lagaan) from the area's farmers. Aamir Khan plays the spirited Bhuvan, a young farmer who leads a protest to the powerless raja. But the protest only inspires the captain to offer the villagers a cynical deal: if |  |

|

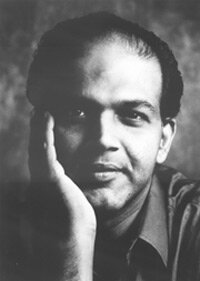

Ashutosh Gowariker, director

(©2002 Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc.) |

|

In combining sympathy for the underdog with a strong visual sense, memorably etched characters, an imaginative music score by the hugely talented A. R. Rahman, and lyrically choreographed dances, Lagaan is replete with all the elements of a Bollywood masala (literally, "blended spices," a term used by |

|

Kulbhushan Kharbanda as the raja (left) and Rachel Shelly as Elixabeth Russell (right)

(©2002 Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc.) |

By several countsmedia hype notwithstandingLagaan has been a significant landmark in the story of Indian cinema. Mounted on a lavish and ambitious scale, Lagaan was a first-time foray into film production for actor Aamir Khan, one of Bollywood's hottest stars, hitherto known for both his box-office appeal and his reputation for hard work in an industry notorious for its indiscipline. Because film production in India is seen as a lucrative way to invest surplus, unaccounted-for profits from other speculative investments, and until recently banks have shied away from financing films, Indian commercial films draw heavily on the larger-than-life image of their stars to deliver box-office hits. In recent years, several major Bollywood stars have attempted to exploit the full commercial value of their image by entering into film production themselves, cashing in on their heightened visibility due to the television boom of the 1990swhen they were regularly featured on TV soaps and as hosts for popular chat showsand drawn by the lure of growing profits in international markets. Made at an estimated cost of US$7 million (a large budget by Bollywood standards) and distributed by Sony

| Pictures, shot entirely on custom-built sets on location over a six-month period, touted as the first Hindi film to feature British actors, and using DTS (Digital Theater Systems) technology to allow for easy dubbing into several languages, Lagaan was evidently made with an |

|

|

Amir Khan as the village leader Bhuvan (center)

(©2002 Sony Pictures Entertainment, Inc.) |

To Indian audiences, the film has been something of an unique achievement. International attention arising out of the Academy Awards nomination kindled national pride, but the reasons Lagaan resonated with Indian audiences clearly went beyond that. Since the early 1990s, there were ample signs that Bollywood was consciously catering to the nonresident-Indian segment of the market in its choice of themes, characters, and settings. Recent "super-hits" fell into two main categories: wholesome family dramas (such as Hum Aapke Hain Kaun, directed by Barjatya, 1994; Dilwale Dulhaniya Le Jayenge, directed by Aditya Chopra, 1995; and Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, directed by Karan Johar, 1995) that peddled consumerist utopias where all signs of poverty and oppression had been wished away through simple narrative choices that depicted lives brimming relentlessly with happiness, wealth, and comfort; or, on the other hand, films espousing a hypermasculine, militant, anti-Pakistani nationalism (Roja, directed by Mani Ratnam, 1992; Border, directed by J.P. Dutta, 1997; Gadar: Ek Prem Katha, directed by Anil Sharma, 2001) that reflected the country's ideological backlash of the past decade and its efforts to redefine India as a Hindu nation. Generally speaking, the Bombay film has never accorded issues of class hierarchy or difference anything more than an ambivalent, clichéd, or populist treatment; yet even by these standards, recent years have seen the topics of caste and class being represented in mainstream cinema with an astounding degree of insensitivity and/or chauvinism. It is in this context that Lagaan gains in significance. True, Lagaan is a period film that can fall back on a somewhat idyllic depiction of village society, and its anti-imperial narrative allows the director a safe distance from contentious contemporary political issues. However, important scenes that highlight the building of the Champaner cricket team (whose star performers on the big daybesides Bhuvanare Kachra, an untouchable, and Ismayelbhai, a Muslim) allow the film to dramatize the challenges of creating a democracy out of a deeply divided society.

Since the 1950s, Bombay cinema has had a loyal international audience. However, with its rerelease this summer in most parts of Europe and Asia and some mainstream theaters in the United States, Lagaan may be Bollywood's first crossover hit. The warm reviews that have greeted the film have been a heartening departure from the usual condescension reserved for Hindi films in mainstream Western media. The reception the film has had marks an important juncture. Critics and mainstream audiences alike may be increasingly exposed to the aesthetics of popular film cultures outside of Hollywood. A step closer, then, toward the engagement between cultures promised by the experiments with the moving image that began nearly simultaneously in different parts of the world just over a hundred years ago.

Veena Naregal is Visiting Faculty at the University of Texas, Austin, and the author of Language Politics, Elites, and the Public Sphere: Western India under Colonialism (Anthem Press, London, 2002).