![]()

TIMELESS HUMOR

Liao Bingxiong and Fang Cheng, masters of a fading Chinese cartoon tradition

by John A. Lent and Xu Ying

The older the Chinese cartoonist, the vaster the difference between him and his younger counterpart in artistic temperament, philosophy, and approach. The wider China opens its doors economically and culturally, the greater the loss or bastardization of uniquely Chinese ways of conceptualizing and drawing cartoons that reach back to Ming (1368-1644) and Qing (1644-1911) dynasties. One needs only to look atand be amused bythe satirical drawings and caricatures that appeared in late-nineteenth-century periodicals to appreciate this vital legacy of drollery and commentary. But in China today, cartooning has strayed from providing a public service or serving as a political watchdog; it has become, for the most part, strictly a commercial venture. Brush and ink techniques have been virtually abandoned, as have literature, folklore, and poetry as content sources. Facial and other features of cartoon characters are now likely to be rendered in the Japanese manga style. All of this has occurred since China accelerated its opening to the West in the 1990s.

These criticisms were heard repeatedly in interviews conducted with dozens of cartoonists in Beijing, Shanghai, and Guangzhou during the past year. Especially vociferous in their comments were two cartoon masters, Guangzhou-based Liao Bingxiong and Fang Cheng, who resides in Beijing.

Eighty-seven-year-old Liao, whose career spans seventy years, quit drawing cartoons in 1995, disgusted with the "unhealthy, meaningless" nature of modern cartooning and what he referred to as the senseless imitation of Japanese manga. A review of Liao's life and work provides clues to what he expects of his profession. Liao, a tall, slender man with a receding hair line, tobacco-stained fingers, and a hearing aid he takes off and adjusts frequently, lives in a modest apartment in Guangzhou. He seems proud of his simple life, pointing out that he can afford a car but does not feel a need for one.

In the spacious Liao Bingxiong Art Gallery, opened in 2000 in the new Guangzhou Museum of Art, sixty of Liao's works are now on view, although, as the artist is quick to point out, he donated two hundred drawings to the government. The museum has seventeen galleries, two of which feature Guangzhou artists; Liao is the sole cartoonist in China to merit his own museum gallery. Liao's career can be divided into three periods in which the focus of his work was, consecutively, opposition to Japan, opposition to Chiang Kai-shek, and self reflection. Liao says the first two periods, which extended from the early 1930s through the 1940s, were "hungry" times, and that he seldom was paid by the Guangzhou newspapers in which his work appeared. "I was very poor and could not afford to take the bus, so I walked to the newspaper to hand in my work. What payments there were, were very small."

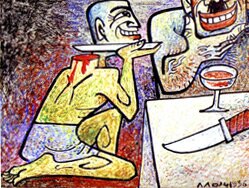

| Beginning with his first published cartoonin Shanghai's Time Cartoon magazine in 1932Liao's work has been hard hitting and bold. Never the lackey serving his head on a platter to a master, as he depicted in a 1936 cartoon (entitled "A Typical Lackey"), Liao tried to be his own man. As veteran Guangzhou political cartoonist Fang Tang, who is in his sixties, said of Liao, "He follows his own feelings, ideas, and opinions on behalf of the common people." |  |

|

Liao Bingxiong, A Typical Lackey, 1936

|

When war with Japan broke out in 1937, Liao, then twenty-three, joined the Cartoonist Salvation Propaganda Team, a small band of independent cartoonists who moved about

|

southeastern China for the next three or four years, using cartoons as a form of resistance and inspiration. Liao said, "I had heard of them, but did not have the money to get a ticket to go to them. Then a photographer friend sold his camera to buy two tickets, and we joined them in Wuhan." After the team disbanded in 1941 when funds from the Guomindang stopped coming in, Liao returned to Guangzhou and drew cartoons for the only paper there that published anti-Japanese material. He also exhibited a series of works as part of a traveling drama troupe he accompanied from place to place. Liao had read Mao's book on waging war against the Japanese and, inspired by it, drew one cartoon for each of the eight chapters. His cartoons would be attached by rope to trees for public viewing before the drama troupe's performances. In the postwar period, Liao was on the run from Chiang Kai-shek's forces, again because of his cartoons, |

|

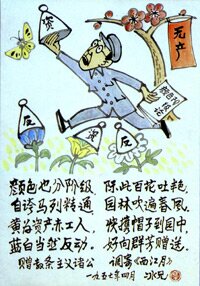

Liao Bingxiong, Colors Also Belong to Different Classes, c. 1958

|

Disappointed with Hong Kong, Liao returned to Guangzhou at the end of 1950, and throughout much of the following decade created thousands of works, mostly political, few of

|

which remain because they were done "just for the occasion under the leftist trend then." But his career came to an abrupt halt after he was labeled a rightist in 1958. Liao had taken Mao at his word when the chairman called for more criticism of the Communist party, and had drawn a series of scathing cartoons. Two in particular that got him into trouble were "Colors Also Belong to Different Classes," in which different colored flowers were delineated as capitalists, workers, and reactionaries, and "To Cut Off His Head for Curing the Scab," in which an overzealous doctor is associated with censors who banned entire literary works because of a single offensive part. According to Liao, Guangdong officials liked the cartoons but the Beijing party leaders expressed extreme displeasure. "Zhou Enlai wanted to protect me, but no one could control the movement; after that, intellectuals were afraid to speak out," he added.

|

|

|

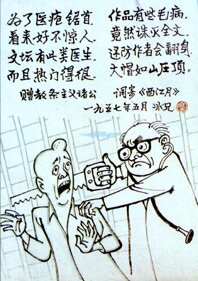

Liao Bingxiong, To Cut Off His Head for Curing the Scab, c. 1958

|

For the next twenty years, Liao did not draw. He was sent to the White Cloud Mountain Farm for reform through labor, and then in 1960 was assigned to the Guangdong Provincial Puppet Art Troupe to work as a set designer. When he did pick up his pen again, in 1979, the

|

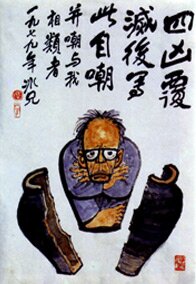

first cartoon he drew was "Self-Ridicule," which has become one of China's most famous cartoons and perhaps Liao's signature work. Enlightened by an article entitled "Practice Is the Sole Criterion To Test Truth," Liao reviewed his own past and depicted himself as emerging from a broken jar, folded tightly, not daring to move. He said the drawing reflected an entire generation of Chinese. "Self-Ridicule" employs the dark colors and strong strokes that are typical of Liao's work, as well as his usual direct message, rare in an environment where subtlety reigns. Other characteristics of his art are decorative elements, serious content, and a folkloric style, traceable to his childhood fascination with Chinese woodblock prints and papercuts. Still active, Liao now creates paintings and calligraphy that are sold to raise money for the schooling of poor children. |

|

Liao Bingxiong, Self-Ridicule, 1979

|

Fang Cheng, another of the few surviving masters of cartooning, also laments the changed cartooning scene in China, stating that the field is filling up with amateurs who do not have drawing skills, do not understand humor as a language, and seldom spend time in intellectual pursuits such as reading. Although many cartoonists in the past did not have formal art training, they were familiar with folk art and literary classics, from which they drew inspiration.

At eighty-four, Fang is an energetic, physically strong, forward-looking individual who is excited about his work and about life in general. He lives in a small, cramped apartment in the

| Chaoyang District of Beijing, not far from the offices of the China Daily. His surroundings are full of art materials, drawings, books, and mementos of his travels around China and in the United States. Fang is extremely productive, putting in long hours seven days a week, not only drawing cartoons, but also painting, doing calligraphy, publishing collections of his cartoons (ten so far), and writing theoretical books on cartooning. The latter he considers very important"to find new ways of drawing" and to pass on his theory of humor and cartoons. Fang says his theory is based on history and on practice, and one of his strongest premises is that humor is the art of language and is characterized by the implied, not direct, approach. By way of example, he said that a sentence such as "When I eat to the full, no one in my family is hungry" implies that the speaker is not married. He prescribed that a cartoonist "must get familiar with somethingand then find the smartest way to say it." |  |

|

Fang Cheng, Chung Kwai's Night Patrol

|

|

In the Western world, the humorous and the funny are the same, Fang said, but in China, they are divided very clearly. "Humor uses language to make people laugh, while funny [art] is without words, like slapstick, like someone falling down," he explained. Fang thinks of humor as an art that must be developed, a quality that "can make people have a sense of beauty." He also said that humor needs freedom, citing the Cultural Revolution when "there |

|

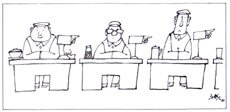

Fang Cheng, The Business Way for Business, 1980

|

Besides writing about humor and cartooning, Fang said his second major task is to do brush and ink paintings that incorporate cartoon-like drawings and humorous poetry. He draws on his self-gained knowledge of classical literature for ideas. "Humor is hard to learn or get," he said. "You must read a lot of books, talk about jokes, listen to humor performances, and keep protecting these humor experiences" so that they do not become extinct. Fang said the Chinese language is permeated with a sense of humor, and the more a cartoonist knows about language, the better his or her cartoons are.

|

Fang pointed out that Chinese cartoons differ from Western cartoons in several respects. Chinese cartoonists cannot perform a watchdog role; for instance, officials cannot be named in cartoons. But as a result of this difference, Chinese cartoons are more apt to be timeless; they do not become outdated and therefore can be recycled almost endlessly. "My cartoons from years ago can still be published now, because they are not news-based," he said. Fang's own cartooning career stretches to the 1930s and was determined, as he says, "by heaven, by the gods." Fang was born in Beijing, but at the age of four moved to his family's ancestral home in Zhongshan County, near Macao, in Guangdong Province. When he was nine, his family returned to Beijing, and he attended middle school there. Originally his goal was to become a doctor, but he did not pass entrance exams for Yanching University (on |

|

|

Fang Cheng, The Close Alliance, 1984

|

|

After graduation, Fang went to work as a chemist in a laboratory in Sichuan Province when "the gods" intervened again: "I was in love with a girl and wanted to marry her, but she said no. I could not sleep or do anything else, so I left and went to Shanghai." Fang said he had seen Shanghai periodicals with their many cartoons and decided he wanted to draw professionally. In Shanghai, he had no job and no |

|

Fang Cheng, Change over Time

|

In 1948, as the Guomindang realized their days were numbered, they made plans to flee to Taiwanhoping to take the most famous artists with them, Fang said. Not wanting to follow Chiang to Taiwan, most artists escaped to Hong Kong, which is where Fang went in 1948. Although he wanted to return to Shanghai after Liberation in 1949, fate changed his course. "There was a sunken ship in Shanghai harbor, so [the ship we were on] went farther north and I ended up in Beijing," Fang said. There, he worked for the Xinman Daily, but recognizing that the People's Daily had the best opportunities for cartoonists, he joined that newspaper and not only drew cartoons but also wrote humor essays.

Liao Bingxiong and Fang Cheng, and a handful of their contemporaries embody a type of cartooning known for its eruditeness, aesthetic beauty, sharp language, and literary allusions. It is our loss that this tradition may be quickly fading away, that most of the cartoons being produced by younger artists in China today exhibit a style and technique that are the equivalent of fast foodbland and forgettable.

John A. Lent has studied and written about Asian mass communications and popular culture since 1964. He edits International Journal of Comic Art and Asian Cinema. Xu Ying is a longtime researcher at China Film Archive who has written extensively on Chinese and other countries' film and animation.