THE RICKSHA ARTS OF BANGLADESH

Conveying the dreams and desires of the man in the street

by Joanna Kirkpatrick

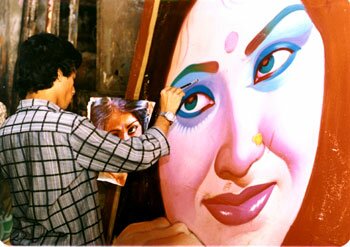

A movie-banner artist touches up his masterpiecethe lush, enticing face of a beautiful woman; she is a film star, a heroine of one of the movies shown in the cinemas of Dhaka and other cities and villages in Bangladesh, and of the daydreams of the typical man in the street.

| Like the wealthy beauties hidden away in their homes or in the curtained, tinted-glass motorcars of the capital city, her eyes are huge and wide. Shadowed in blue, they penetrate the heart. She is but one example of the movie posters from which the images that decorate the rickshas of Bangladesh are taken. Ricksha art, like the movie banners and advertising posters from which it derives, is a popular medium that reflects the heart's desires of ordinary men and, as one ricksha maker told me, is, indeed, |  |

|

A movie-banner artist at work |

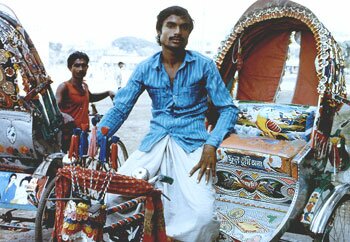

The cycle ricksha was introduced to East Bengal (now Bangladesh) around the end of World War II, when the area was still part of the British Indian Raj. The three-wheeled pedicabs are built on an elongated bicycle frame; the driver sits on a cycle seat in front and pedals the

|

|

|

|

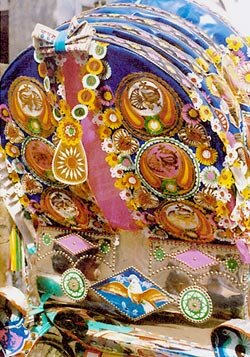

The back and front of an elaborately decorated ricksha, Dhaka, 1987

(photo by Joanna Kirkpatrick) |

||

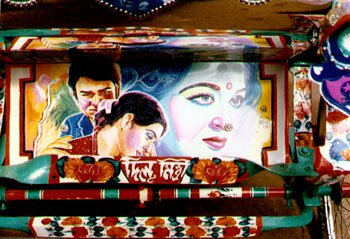

Ricksha art began to proliferate in the 1950s, when this part of Bengal was East Pakistan. Ricksha art employs multiple themes, materials, and intentions; it is a hybrid of folk art and commercial designs, combined with ideas from the individual artist's imagination. At first, some ricksha owners pasted movie posters on the backs of the vehicles; the decorations later became more elaborate when paintings of movie actresses who appeared in popular films from Lahore, in West Pakistan, were featured, often accompanied by verses from the movie's songs. Tigers and animal combat themes also became popular. After the new nation of

| Bangladesh declared independence in 1971, paintings with political themes began to appear; topical subject matter included children saluting the new nation's flag, rape-killings of Bangladeshi women committed by Pakistani soldiers during the liberation war, or scenes of lungi-clad Bangladeshi guerillas in combat with uniformed Pakistani soldiers. In reference to the U.S. moon landing of 1969, pictures of an astronaut planting a Bangladeshi flag on the moon appeared. |  |

|

Movie material on a ricksha backboard, Dhaka, 1987 |

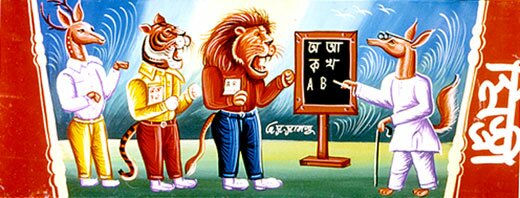

Although many of the subjects portrayed in ricksha art continue to be emblems of male desiresex, competitive power, and wealththere are also universal themes, such as longing for the village home, for the blessings of religious devotion, for material possessions (for example, shiny red sports cars or enormous mansions), and occasionally, as at the very beginnings of Bangladesh in 1971-72, for solidarity and identity with Sonar Bangladesh (golden Bangladesh), the new nation with its Bengali language and traditions. Ricksha art images can also suggest frustrated desire, expressed as satire in some pictures, in which animals, behaving like people, mirror the foibles of men or, perhaps, say what is politically unsayable.

|

|

Uncle Jackal's Lesson: mocking the tyrannical schoolmaster

(photo by Joanna Kirkpatrick) |

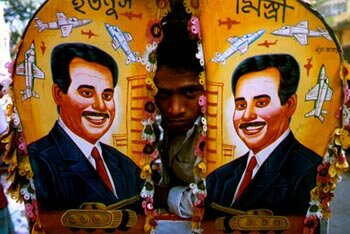

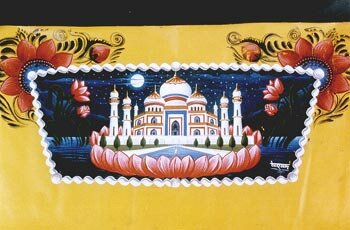

As I noticed during a number of visits between my first year in Bangladesh, 1975-76, and my last visit, in 1998, pictorial themes often reflect current politics, both local and international. For instance, in 1992, after the Gulf War, the face of Saddam Hussain adorned ricksha backboard and hood panels. However, the perennially popular themes are movie stars, animals, animal fables, city scenes, and religious themeslike a Taj Mahal, or a mosque, floating on a lotus, symbolizing Muslim identity and Bengali culture. Artists paint backboard panels with enamel paints on recycled tin sheets; in the case of movie-star images, they use posters as reference material. Elaborate niches outlined with nailheads and filled with inset

|

painted designs or movie postcards are placed below the seat. The ricksha's metal framework is usually ornamented with conventional creeper and flower-vase designs. Its collapsible hoods are covered with colorfully painted and/or appliquéd plastic medallions and decked with plastic ruffles. The footboard extending below the seat is variously ornamented, and the passenger seat is upholstered with plastic material on which even more pictures are painted. |

|

Saddam Hussein, Dhaka, 1992

(photo by Kevin Bubriski) |

During the 1970s and 1980s, ricksha decoration expanded profusely. The 1980s represented the heyday of ricksha art. By the 1990s, the number of people and motorized vehiclescars, buses, trucks, and motorized three-wheelersin Bangladesh's big cities had proliferated to such an extent that they clogged the main streets. Rickshas, the preferred and affordable mode of transportation for the ordinary citizen, had also proliferated, and in Dhaka in the 1990s numbered approximately one million. Inevitably, cycle rickshas were banned from many of the city's main roads as impediments to the smooth flow of traffic. The banning of rickshas from major roads, along with the advent of mass-produced photographic printscheap substitutes for the hand-painted pictures on the backboards of the passenger cabshave taken their toll on ricksha art in the nation's capital. Ricksha decoration still flourishes in smaller towns, where there are not as many motorized vehicles and rickshas still have room to ply the streets. However, Dhaka is the city where ricksha art reached its apex of development and beauty, supplying models of decorative design to the rest of the country. A decline in the number of rickshas in Dhaka, and in ricksha art there will, I suspect, result in a similar decline throughout the country, as a result of increasing economic development.

Most ricksha artists are self-taught, although some individuals will apprentice with a master artist and then open their own business. Women have little involvement in ricksha arts, except as home helpers. (Of all the ricksha artists I met, or heard of from Bengali friends and colleagues, I knew of only one young woman who had been trained by her father to a professional ricksha art standard as a picture panel artist.) Some say that the reason they chose this occupation was because it seemed a reliable way to make a living that enabled them to stay at home with the family. Some ricksha artists also paint the banners that are hung above the entrances to movie theaters, but most of them only do ricksha decor. The owners of fleets of rickshas usually commission decoration from a mistri (maker) who works in his own shop, often with living quarters behind it, and is in charge of assembling the entire ricksha. But an artist might be individually commissioned by an owner, or by a mistri, to decorate a machine according to the owner's demand. Some renowned artists are invited to paint what they please. Lesser-known artists paint batches of backboard panels that are stocked for sale in ricksha supply stores. These backboard panels are used either in the construction of new rickshas or in refurbishing. After the fad for decorating rickshas became established, some owners of big fleets began to compete with one another for name and fame as owners of gorgeous rickshas. Each had his "mark," or emblem, painted on the back of the machine.

There are definite class distinctions in ricksha art. Fleet owners are usually members of the gentry, while both the mistris and the artists are members of the lower-middle class. Upper-class Bengalis, especially women, often say they do not even "notice" ricksha art. Many of them consider it vulgar, not really "art." After all, Bangladesh has many famous fine artists, both painters and sculptors (most of whom, incidentally, although their own work favors abstraction, like ricksha art). The ricksha people, however, believe that they are indeed making art. Gradually, as development organizations with foreign staffs burgeoned in the country, ricksha art attracted so much attention from foreign expatriates that the Bengali gentry could no longer completely ignore it. Expats happily commissioned romantic paintings, on panels, of themselves and their spouses, based on photographs. One expat doctor I know commissioned a ricksha artist to decorate the exterior of the trunk of his automobile.

Communicating with artists through my Bengali assistant, I would ask them to tell me what their pictures were about or why they chose the subject matter, but they avoided comment, mostly saying in effect, "We just paint what we're asked to do." But they were articulate in stating the names of the various picture themes: movie scenes, animal scenes, village scenes,

| city scenes, Taj Mahal scenes, freedom fighter scenes. I inferred that religious piety may have been the reason for their reluctance to talk about ricksha art, for the most commonly cited collection of traditions (hadith) of the prophet Muhammad, a collection known as Sahih al Bukhari, says: "Among those who will be most punished by God on the Judgment Day are the artists . . . ," that is, makers of figurative imagespainters and sculptors. Art making is thus felt to be close |  |

|

The Taj Mahal on a lotus, Dhaka, 1987 |

|

Due to the growing Islamization of Bangladesh since the late 1970s, ricksha art has become a contested occupation. Why has Muslim Bangladesh created elaborate conveyance arts, while Hindu India or Buddhist Sri Lanka have not? Perhaps the over-the-top flamboyance of the country's ricksha art is a sign of the "return of the repressed." This is a psychological state that, in the case of art, is based on the human longing to see desired objects and figuratively to possess them. The act of looking at figurative |

|

A ricksha driver, Dhaka, 1982

(photo by Joanna Kirkpatrick) |

Joanna Kirkpatrick is a social and cultural anthropologist. Now retired from Bennington College, where she taught for almost thirty years, she continues research and writing on popular arts and conveyance arts worldwide, with special focus on South Asia. Her Web site is www.ricksha.org .