THE BLUE JACKET

by Gao Ertai

|

People who scratch a living from alkaline soil have a stricken look. Their skin, blasted by the alkaline wind, is shriveled. Their feet, soaked in alkaline water, are covered with cracks. Their clothes are coated over with alkaline dust; the colors fade and the fabric disintegrates. The group of us, sent down here from the four corners of the land, have over time melted into one gray mass, old and young alike, hardly recognizable one from the other. It is easy to spot a newcomerhis clothes are intact and the color stands out against the dreary background of us old-timers. But there are exceptions. Long Qingzhong of the Third Brigade was decidedly an old-timer, but his jacket was just as tidy as it had been on the day he arrived. You could pick him out |

|

|

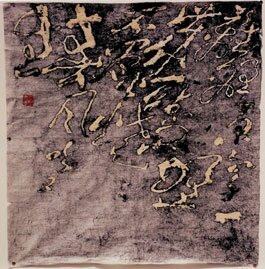

Gao Ertai |

Long didn't shirk work, but being so fastidious about his jacket did sometimes hold him back. He was often criticized for this failing at the team meetings, but it didn't do any good. He was also criticized at higher-level brigade meetings. Once the director of our Farm, Comrade Liu, calling Long by name, said, are you here to find a girlfriend or what, causing a faint, hesitant ripple of laughter among us. But for Comrade Liu, this was mild language. In the same speech, he actually went on to praise Long. It turned out that in a letter to his mother opened during a routine inspection of our private mail, Long had described the Farm in glowing terms, reassuring her how happy he was to be here. Comrade Liu pointed out that this was solid proof that Long was making good progress in thought reform. With such an honor to his credit, no one could really touch Long, jacket or no jacket.

I first came across Long Qingzhong at a "Great Match," one of the tricks devised by the Farm leadership to raise productivity. They would stake out a piece of wasteland and divide it into sixteen columns, marking out the boundaries with chalk; each column was about as wide as a regular highway, and three hundred meters long. That was the stage on which the match would take place. Each of the sixteen work teams on the Farm would send out a representative to turn over the soil. The race between them was intense, but except for a few thought-reform officers, there were few spectators. Wethe masseswere assigned to work in a neighboring field, digging a ditch to reduce the alkali in the soil. Our progress would be reported in "Express from the Work Front," a newssheet put out by the labor reform authority. If we exceeded our quota, the credit would go to the team. As for the individual who made the greatest contribution, he would be rewarded with a heavier workload the next day.

Long wore thick glasses. He was thin as a reed; his famed blue jacket hung loosely on his slender frame. I suggested that he tie a length of straw rope around his waist to keep out the wind. "Oh no," he replied, "this is real khaki; it can't stand any rubbing, let alone the wear and tear of a belt of straw." He showed me where the fabric had become worn at the cuffs, shoulders, and elbows. He caressed the worn spots as if caressing wounds. The sleeves of the jacket had to be turned up for work, thus exposing the white lambskin lining. Specks of dust on lambskin cannot be shaken off, the harder you try, the deeper they get embedded. Now and then Long would take off his glasses and almost bury his nose in the lining, trying to dislodge the alien particles. During the break, he dared not lie down but just dozed a little in a sitting position. I lay flat on my back and took a good look at him. His scraggy neck, sunken cheeks, loosely hanging jaw and the drooping corners of his mouth all bespoke extreme exhaustion and physical debility. But he sat doggedly upright, rejecting my advice to lie down and stretch out. No, his jacket was more important.

When I dozed off, he would keep silent. When I couldn't sleep, he would talk. He had a slight stammer, and told his tale slowly, in driblets, talking as much to himself as to me. He was an only son, and had been brought up by his widowed mother through great hardships. He graduated from university with a degree in biology and was then assigned to the Lanzhou branch of the Academy of Sciences. His research on prairie parasites often took him away on field trips. Back at the Academy, he ate at the canteen and slept in the communal dorm. Going on thirty and still unmarried. His main concern was to arrange for his old mother, back in rural Hebei Province, to join him in Lanzhou city, so that they could be together.

Long's mother was a villager, what is called a rural resident, and by government regulation, could not move to the city except by special permission. Long could make no sense of such a regulation. Missing home, he applied to be transferred to his native Hebei. But at the time, the government was intent on developing the Northwest, and it was hard to get permission to move in the opposite direction, from west to east, not to mention the fact that Long was much needed at his work unitone's personal wishes must give way to the greater good. The leaders lectured him: you have been raised and reared by the labor and sweat of the working people, but all you can think of are your own individual wishes, now what kind of attitude is that? Long had no answer; he was unhappy, and frequently grumbled under his breath.

During the anti-Rightist campaign, Long's work unit could not find enough scapegoats to fill its quota of Rightists, so after going through the required struggle meeting, which was the standard procedure to qualify someone a Rightist, they slapped him with the label. He was then sent here to the Farm for thought reform. He dared not tell his mother the truth. For the first time in his life, he lied, writing to her that he was going on a field trip that might last longer than usual and that she was not to worry. The day before he left, he received a package from his mother; it contained the blue jacket for which he was famed throughout the Farm. The style was old-fashioned; the jacket was very wide down to the waist, and the stitches were uneven since his mother had poor eyesight. But it was firmly stitched together, made to last.

His story moved me deeply because I, too, missed my mother. After that incidental meeting at the Great Match, I never saw him again, but I often thought of him. This was during the Great Famine of the early 1960s; daily, people on the Farm dropped dead in the fields without any warning. Long was weaker than most, and I feared that he could not survive. As I worked in the fields, I would often glance in the direction of the Third Brigade. Whenever I saw that striking blue jacket among the masses of gray, my heart would be at ease. I believed that it was his mother's love that gave Long the will to survive. The force of Love was stronger than Death, I thought to myself.

Finally, winter was over, and spring arrived. One evening, I went to the clinic to change my bandages. I was walking across the basketball court when I saw Long Qingzhong walking ahead of me, with a length of rope tied around his waist. He's finally done the sensible thing, I thought happily as I hastened to catch up with him. But when he turned, I realized the man in front of me was a stranger. He told me that Long had died long ago, and the fellow inmate who had taken his jacket was also dead. By the time the jacket ended up with him, he added, it had passed through many hands.

Translated from the Chinese by Hong Zhu

Gao Ertai, born in 1935 in Jiangsu province, is a writer, painter, and art critic, and a scholar best known for his contributions to aesthetics. He has been on the staff of the Research Institute of Cultural Relics in Dunhuang, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences Institute of Philosophy, Lanzhou University, Sichuan Normal University, Nankai University, and Nanjing University. In 1957, after the publication of his article "On Beauty" and other essays, he was labeled a "Rightist" and sent to a labor camp. In 1966, he was again sentenced to hard labor, until 1972. He was exonerated in 1978, and in 1985 was recognized by the National Science Council as a "State Expert with Distinguished Contributions." He was again imprisoned in 1989, for antirevolutionary writings. After his release, he left China and now lives in exile in the United States. He is currently a fellow at the International Institute of Modern Letters, University of Nevada, Las Vegas, where he is writing his memoirs and continuing to paint. "The Blue Jacket" is from his memoirs.